Mel Roberts told me he is surprised by the resurgence of interest in his photography. It first appeared in

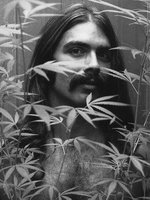

Young Physique magazine in 1963. From the 1950s to the early ‘80s, he used two Rolleiflex cameras to take an estimated 50,000 photographs of nearly 200 models. Most of them were friends. Many were lovers. Now at age 82, his memories of them are as sharp and vivid as

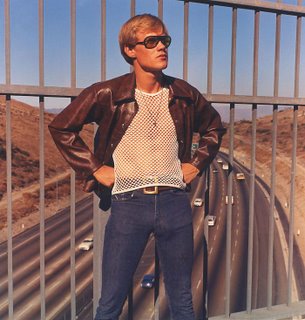

the color prints he made decades ago.

They weren’t the perfectly proportioned bodybuilders, hustlers, or professional models common in the magazines of the time and typical of AMG and Bruce of LA. Before the “Nautilus” was invented, working out at the gym was an unusual activity for a young man (gay or straight). Roberts preference was for more natural “everyday” guys, rarely older than 25. Although they were paid, they really posed for the fun of it.

Roberts recalls: “I tried to make it as enjoyable as I could. We’d go off to Yosemite or Idlewild or La Jolla on 2 or 3 day trips.” But he had to know them as friends first. “I could never just come right out and ask them to model. So very often I’d invite them over for dinner. They'd meet my friends and become a part of the ‘family’ before I'd take my first picture of them. When we did ultimately go out into the field they felt so comfortable with me and so relaxed it was reflected in my work.”

This was the vision that distinguished Roberts’ work and brought him rapid success in the U.S. and Europe: Beautiful sun-tanned guys casually posed by the pool, or against the backdrop of Southern California’s stunning natural environment. If their varying states of undress come across as a photographic striptease, it was intentional. The erotic narratives they suggest reflected the reality of their making. Sexual adventure was part of the package and everyone was having a very good time.

It was a different era: Certainly not innocent― but not nearly so cynical as our own. We might look back wistfully at this period of openness and experimentation, before AIDS, before sunscreen, before the 405 became permanently choked with cars. You could hitch a ride to LA, go to a party, pass a few joints, take off your clothes, and have sex, just because you felt like it. One writer called Roberts the ‘Hugh Hefner’ of the gay world. “I always had four or five guys living with me at one time. They had no prohibitions, no guilt about having sex with guys, even though most of them had girlfriends who were also frequent visitors.”

But it wasn’t all fun and games. This was still the “posing strap era” when taking a picture of a naked man could land a photographer in prison. Roberts had to build his own color lab to develop prints because no lab would process the film. The transparencies he sent to Eastman Kodak were returned to him with holes punched through the genitals of the models.

“I knew I was taking a chance. But I thought, I live just a few blocks from the Playboy Mansion, and here’s Hefner showing nude women, so what’s wrong with me showing nude men? I never thought there was anything wrong with being gay.”

But in the 1950s, police harassment and raids were commonplace. Roberts heard about Harry Hay and the Mattachine Society, and started having meetings at his house once a month. Just a few guys at first, but as word got out, more and more men started coming by. “We tried to make sure that guys who got arrested knew their rights: To remain silent, to demand a jury trial, etc. But if your employer found out you were gay, you got fired anyway.”

It wasn’t until 1977 that the LAPD went after Mel Roberts. Under the false charge that Roberts was photographing underage models, they showed up with a warrant and raided his home and studio. They confiscated his cameras, negatives, letters and even his mailing list (which effectively put him out of business).

“We stood in the driveway in handcuffs from 10:00 in the morning to 6:00 at night as they loaded everything into a truck. I couldn’t even return the money my customers had sent me because I didn’t have their addresses.” A second raid followed, 18 months later. The LAPD refused to return his property for over a year, even though no charges were filed against him.

But this pointless harassment took its toll, and besides, times had changed. The California Dream that Roberts’ work epitomized for many gay men was just a memory. His photographs were considered “too tame” to be published. The AIDS epidemic was spreading. His friends started dying. He put down his camera for good. But his story wasn’t over.... more to come.

Check out Mel Roberts' vintage prints of California men at

homobilia.com